This White Paper has been organized into the following subsections:

- Section 1: Introduction

- Section 2: Factors that May Influence a State’s Ability to Address CEC

- Section 3: Current CEC Programs and Approaches

- Section 4: A New Framework for Identifying and Monitoring CEC

- Section 5: Closing

1. Introduction

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) and state environmental or health regulatory agencies (collectively referred to as states) are tasked with protecting human health and the environment. As part of this mandate, both USEPA and states regularly develop guidance and/or regulations that serve to limit public exposure to contaminants in the environment. USEPA water quality programs that may serve as good resources can be found at the following link: Contaminants of Emerging Concern including Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products | USEPA. States may also develop programs to monitor and identify potentially harmful substances that could be present in the environment. These substances could include contaminants with known occurrence but limited exposure and toxicity information, contaminants with limited to no data on potential presence in the environment or potential toxicity, or known or existing contaminants with new exposure or toxicity information. Understanding the potential exposure, toxicity, and fate and transport of these contaminants is critical to assessing risk and, in turn, risk management options for protecting human health and the environment. This document is intended to provide guidance on how to identify and evaluate contaminant(s) of emerging concern (CEC).

This White Paper and the four associated CEC Fact Sheets provide a framework that may help states make decisions when undertaking or developing a program to identify, evaluate, and monitor potentially harmful substances in the environment. This framework can be used whether or not a state has a formal CEC program. A state’s interest in taking action may be driven by the potential risk posed by a CEC. Ideally, the goal of any CEC monitoring program should be to shorten the time from the identification of a CEC to risk mitigation, thereby minimizing the potential risk to human health and the environment.

Protecting public health and the environment may include identifying and evaluating CEC present in environmental media (e.g., soil, groundwater, surface water, air, biota), even when only minimal information is available. Patterns of use and disposal may cause CEC to end up in one or more environmental media. States can more easily track concentrations of contaminants in the environment with a CEC program. In some cases, CEC monitoring programs may allow corrective actions and regulatory responses to be implemented before potential exposures and adverse human health or ecological effects occur (NSTC, IWG-EC 2022) (IWG-EC, January 2022). Developing a CEC program may also provide opportunities for states to address environmental justice issues such as improving water quality in disproportionally impacted communities.

This White Paper addresses three broad topics:

- factors that can influence a state’s ability to address CEC

- current CEC programs and approaches

- a new framework for identifying and monitoring CEC

For the purposes of this White Paper and four associated Fact Sheets, CEC are defined as substances and microorganisms, including physical, chemical, biological, or radiological materials known or anticipated to be in the environment, that may pose newly identified risks to human health or the environment. This definition aligns with the language provided in the USEPA Memorandum, “Implementation of the Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Fund Provisions of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law [BIL]” dated March 8, 2022. Per the definition provided in the USEPA Memorandum, CEC “can include many different types of natural or manufactured chemicals and substances — such as those in some compounds of personal care products, pharmaceuticals, industrial chemicals, pesticides, and microplastics.” The definition incorporates many substances listed on the Contaminant Candidate List that can be addressed with drinking water state revolving funds. The USEPA memorandum provides guidance for obtaining funding to address CEC (Fox 2022), and more information can be found in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law SRF Memorandum | USEPA. States that identify CEC in a manner consistent with the USEPA’s definition and meet various other requirements may use funds from the BIL to develop programs and projects that address a wide variety of local water quality and public health challenges. These can include addressing CEC in drinking water and wastewater discharges, investing in ecological challenges, or addressing public health challenges experienced by disadvantaged communities.

A chemical may no longer be considered a CEC when one or more of the following criteria have been met: (1) the chemical can be analyzed using validated analytical methods, (2) the chemical’s toxicity has been evaluated/identified, or (3) the chemical has regulatory screening levels. The specific decision on when a chemical is no longer considered a CEC will be up to each individual state to determine.

The approaches and discussion provided in this White Paper are further detailed in four Fact Sheets, which are discussed in Section 1.4. This White Paper and the associated Fact Sheets provide a framework for states to consider when developing a strategy for additional data collection and monitoring (CEC Monitoring Programs Fact Sheet), evaluating and prioritizing exposure and potential to cause toxicity (Identification of Key CEC Variables Fact Sheet and Adoption of Analytical Methods for CEC Fact Sheet), and communicating information to the public and other stakeholders in a timely fashion (Risk Perception and Communication Fact Sheet).

The definition of CEC covers a wide range of substances, including biological and radiological materials, but this White Paper and the CEC Monitoring Programs Fact Sheet, Identification of Key CEC Variables Fact Sheet, and Risk Perception and Communication Fact Sheet focus more on chemical CEC as a starting point to address the issue. Nevertheless, the concepts presented in this document also apply to other types of CEC (e.g., biological), and the Adoption of Analytical Methods for CEC Fact Sheet, which provides a summary of CEC analytical methods, addresses a wider range of CEC.

2. Factors that May Influence a State’s Ability to Address CEC

The Interstate Technology and Regulatory Council (ITRC) CEC Team developed and distributed a 21-question survey when the team was formed. The survey was designed to gather information that would help the team understand the variety of efforts and resources that state agencies are currently directing toward CEC programs and what additional information is needed. Thirty states and five federal agencies responded. Respondents identified the following key issues:

- Several states do not have or use databases to track or assess specific CEC but would find such tools useful.

- Funding, staff resources, guidance, and agency/legislative support are critical to launching a formal CEC program.

- Several states do not have their own process to identify and evaluate characteristics of CEC for prioritization.

The information obtained from the state survey was used as a general guide for the discussion below and discussions presented in the Fact Sheets. Other factors identified in the state survey that could limit development of a CEC program, such as state-specific bureaucracy, legislative support, and other regulatory issues, are not addressed further in this White Paper or associated Fact Sheets.

2.1 Available Information About a Potential CEC

Gathering information on CEC can be a challenging and time-consuming process that may require staffing and expertise that are not currently available within many state organizations. The options available for establishing regulations or guidance for a CEC are heavily dependent on data sufficiency and sharing. For some states it may be possible to conduct comprehensive literature reviews, prepare research articles and reports, and review regulatory databases to identify substances that have recently gained attention as potential CEC.

In particular, when CEC have been identified through monitoring, information on distribution and/or toxicity may be very limited1. Moreover, in many cases, there is not enough information to evaluate risk using standard regulatory approaches, as most CEC have not been sufficiently studied to fully assess their toxicity. The chemical may still be considered a CEC if it may pose a potential risk pending further investigation. Even when some toxicity information is available, that information may not be adequate to permit the calculation of a toxicity value (e.g., reference dose, cancer slope factor, or ecological effects threshold) that is scientifically supportable using standard risk assessment methods, and it may be necessary to use a surrogate or other modeling approaches (See the Identification of Key CEC Variables Fact Sheet).

The Risk Perception and Communication Fact Sheet provides some guidance on addressing situations with little data and high potential consequences.

2.2 Communication, Public Concern, and Coordination

Stakeholders play an important role in the process of identifying and addressing CEC, but communicating information about CEC with internal and external stakeholders can be challenging. More details on strategies for communicating with stakeholders are provided in the Risk Perception and Communication Fact Sheet. Below is a brief discussion of the variety of communication challenges that may develop.

2.2.1 Importance of Effective Communication and Outreach

The local community and public are often alerted to a new CEC via news or social media, which may give the impression of a long-ignored problem or may paint the issue in alarmist terms. This may generate fear and distrust. Regulatory agencies and responsible parties should engage with the local community early and establish information to be shared with the public and open lines of communication as soon as a new CEC has been identified using a CEC identification framework or process such as one presented in the Identification of Key CEC Variables Fact Sheet. Technical and health experts should be made available to address public concerns. These experts, together with a risk communicator or health educator, need to have a plan for communicating the risk associated with the CEC, including uncertainties such as data sources, unknowns, assumptions, etc. (see the Risk Perception and Communication Fact Sheet). Use of social media and well-publicized websites for frequent information sharing, combined with prompt and effective responsiveness to questions, are essential in the early stages when there may be a high fear factor. Engaging with local community organizations is also helpful. Finally, it may be advisable to regularly hold meetings with the community based on the phase of the CEC or the level of public concern.

In a world with instant information sharing, the public fear factor is easily raised and can be challenging to address. A useful way to address fear and public outcry is by listening to and accepting public concerns and developing prompt responses that reflect knowledge and awareness and are presented in clear terms and straightforward language. Effective dialogue is not achieved through one meeting or media release; fear and outcry can only be reduced through frequent communications. If the specific fears and concerns of the public are known early in the process, it may be possible to effectively address the public’s concerns if the high-profile individual is willing to learn more about the issues. Otherwise, further public interaction is necessary. Refer to the Risk Perception and Communication Fact Sheet for a more detailed discussion about communication with the public.

2.2.2 Coordination with Other States, the Federal Government, and Academia

A state advisory council that includes representatives from the applicable scientific disciplines and state and federal government agencies should be formed to facilitate information sharing and development of a road map to guide scientific and legislative processes. Including representatives from the health care system, such as state and local health departments, hospitals, and physicians, as well as environmental departments and similar organizations, should also be considered. These agencies and sectors, which are often viewed as a trusted source, could provide critical help when disseminating information about CEC to the public. The elements of the road map will identify the types of information required and facilitate sharing of ideas between agencies and experts. The process of investigating and addressing CEC is a complex multi-year effort. It is important to communicate consistently in clear, plain language. Communications should be provided in English and in other languages as appropriate based on the limited English proficiency data for the impacted community. Communications should also be accessible to those with hearing or sight disabilities. Because states may have different risk concerns, it is important to recognize and consider local expertise, including the lived experiences of community members. States should have at least one identified CEC point of contact and a mechanism for information transfer among agencies.

2.3 Funding

Funding for state CEC programs, monitoring, and investigative activities can include two major sources: state and federal funds. State funding for CEC is dependent on the priorities and policies of the state. Funding for CEC can come from state laws that give state agencies the authority and funding to establish a CEC program or otherwise monitor and characterize CEC. State CEC programs are often established gradually, with an assortment of federal and state funding sources; therefore, acquiring appropriate funding may be a challenge when a program is first established.

The second major source of funding is federal laws that provide funding for specific programs. Federal funding is typically assigned a steward such as USEPA or the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which has the financial processes and resources to control the distribution of the funding. Grant managers should be familiar with federal and state accounting regulations.

The BIL is an example of federal funding that can be used for CEC. BIL funding includes $5 billion in principal forgiveness loans and/or grants for drinking water and clean water state revolving funds. USEPA oversees both the Drinking Water and Clean Water State Revolving Funds, and each of the 50 states and Puerto Rico operates its own Drinking Water and Clean Water State Revolving Fund program. The specific procedures and uses of BIL funding are captured in detailed guidance provided by USEPA to state funding authorities.

Another example of federal funding that could be used for CEC is the CDC’s State Biomonitoring Grant Program. The CDC’s Division of Laboratory Sciences administers the National Biomonitoring Program, which assesses the exposure of U.S. populations to environmental chemicals and toxic substances (https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/index.html) (CDC 2022). This program can be used by the states to set up laboratories and to fund the collection of samples that would enhance understanding of human exposure to and the fate and transport of chemicals in the environment.

USEPA and other federal agencies are working to address environmental and public health challenges affecting historically underserved communities. These include communities adversely impacted by persistent poverty, inequality, and lack of funding/resources (Fox 2022). One mechanism for addressing these challenges is the environmental justice program, under which several grant programs have been established to help states and other entities better serve these communities (OEJECR USEPA 2020). Other federal and state funding is available for addressing CEC, but a comprehensive list of funding opportunities is beyond the scope of this document.

2.4 Other Factors to Consider

Despite these challenges, states may still seek to proactively address CEC or develop a CEC program based on external influences/considerations. In the face of limited scientific and regulatory information, state environmental and human health experts may leverage their participation in national networks like ITRC, the Environmental Council of the States, and other organizations to amplify technical understanding of CEC, identify policy options to address CEC, and direct resources available to fund responses to CEC. High-profile events may also have the potential to redirect public resources and political will toward addressing CEC and improving the capability for appropriate responses to future CEC detections.

3. Current CEC Programs and Approaches

When determining whether to set up a CEC program or evaluating CEC data, states may wish to consider existing programs and review approaches developed by other federal and state agencies. States can learn how these existing programs or approaches have tackled the factors discussed in the previous section. The Association of State and Territorial Solid Waste Management Officials developed additional guidance related to developing a CEC monitoring program that may be worth considering (2023-01_State_CEC_Program_Guide.pdf (astswmo.org)). Several existing programs that have considered these factors are briefly summarized in the following sections.

3.1 State Programs

In general, state environmental agencies have the mission to protect the environment and public health. States use a variety of approaches, which depend on priorities and resources, to monitor, address, or regulate CEC. These approaches range from basic identification of specific CEC as a potential concern based on properties of persistence and bioaccumulation to development of a weight of evidence approach that considers a wider range of variables. A few states also have programs (e.g., California) that focus on preventing the upstream use of chemicals in manufacturing, consumer products, or other processes that have the potential to release chemicals to the environment. Discussion of these types of programs are beyond the scope of this project. Additional details on state CEC programs can be found in the CEC Monitoring Programs Fact Sheet.

The following established state programs focused on CEC are provided to serve as useful examples. This section is not meant to be exhaustive; a more complete list of state programs can be found in the CEC Monitoring Programs Fact Sheet.

California has a CEC Program that is a joint effort of the California State Water Resources Control Board and the Regional Water Quality Control Boards. The California CEC Program is developing a statewide plan that applies a data-driven process and a risk-based framework to prioritize CEC for assessment, monitoring, and management. This approach has been used to support recommendations for monitoring CEC in aquatic ecosystems and potable recycled water. The CEC Program is working to support useful data collection and data transparency through development of statewide CEC data management and quality assurance program plans. The CEC Program is also working with interagency partners to leverage resources and develop collaborative solutions to address CEC using an approach that considers the impacts of chemical management from product sourcing, manufacturing, transportation, use, and disposal.

Minnesota has been monitoring CEC in its water resources and has had a dedicated program to develop health-based guidance for CEC in drinking water since 2009. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) monitors for CEC in groundwater annually and in its rivers and lakes every five years in connection with the National Aquatic Resource Surveys conducted by USEPA. The MPCA established a process for developing Aquatic Toxicity Profiles (https://www.pca.state.mn.us/water/contaminants-emerging-concern) (MPCA 2023) that provides a review of information about a CEC and then ranks it using a weighting formula for comparison with other CEC. In addition, the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) uses a quantitative scoring system to establish priorities for emerging contaminants identified in surface and groundwater and generates health-based guidance for identified CEC (https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/environment/risk/guidance/devprocess.html) (MDH 2022). For CEC with limited information, MDH describes the hazard posed by the CEC instead of generating a health-based guidance.

Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (MI EGLE) regulations require owners and operators of contaminated properties to consider CEC when taking actions to eliminate unacceptable exposures from contamination (MI EGLE-RRD Due Care Guide) (EGLE 2019). If a CEC has no established cleanup criteria, owners and operators are required to evaluate the detected chemical against a state cleanup standard. The state cleanup standard is developed by (1) using USEPA screening levels or risk-based criteria developed by MI EGLE and (2) determining availability of an analytical method.

3.2 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Approaches

USEPA has processes for addressing chemicals that are not currently regulated. These processes can serve as sources of information for identification and evaluation of CEC. Key programs that USEPA uses to monitor and/or evaluate CEC are associated with the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) and the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA). Under each of these statutes, USEPA has developed regulations and guidance to address CEC. Additionally, USEPA has instituted voluntary programs for phasing out or reporting CEC.

First, under the SDWA, USEPA’s Office of Water is required to develop a Contaminant Candidate List (CCL) that identifies priority contaminants for regulatory decision-making and information collection (OW USEPA 2014). The CCL is a list of drinking water contaminants that are known or anticipated to occur in public water systems but are not currently subject to USEPA drinking water regulations. The SDWA directs USEPA, when developing the CCL, to consider the health effects and occurrence information to identify the contaminants that present the greatest public health concern related to exposure from drinking water. The USEPA must decide whether to regulate five or more contaminants on the CCL list, a process known as regulatory determination (https://www.epa.gov/ccl) (OW USEPA 2014). In addition, USEPA uses the CCL to prioritize drinking water research and guide decisions about which contaminants to monitor for under the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR) (https://www.epa.gov/dwucmr) (OW USEPA 2015). The UCMR requires that every five years, large public water systems, small public water systems between 3,300 and 10,000 people (subject to the availability of USEPA appropriations and sufficient laboratory capacity), and a nationally representative sample of small public water systems serving less than 3,300 people monitor for up to 30 unregulated contaminants. This monitoring is used by USEPA to understand the frequency and level of occurrence to support future regulatory decisions to protect public health.

Second, under TSCA, USEPA has developed a Chemical Prioritization Process for Risk Evaluation (OCSPP USEPA 2023). TSCA requires that when identifying candidates for the prioritization process, 50% of all high-priority designations be drawn from the 2014 Update of the TSCA Work Plan (OCSPP USEPA 2014) and that USEPA give preference to Work Plan chemicals with the following characteristics:

- high persistence and bioaccumulation

- known human carcinogens

- acute or chronic toxicity at low doses

Aside from these statutory preferences and requirements, USEPA has discretion to determine which of the thousands of active chemicals to prioritize for risk management.

3.3 Department of Defense Approach

In 2006, the Office of the Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Installations and Environment initiated a program to proactively minimize adverse impacts from emerging chemicals (ECs) to human health, the environment, and vital Department of Defense (DOD) mission areas. ECs are defined by DOD as “chemicals relevant to the DOD that are characterized by a perceived or real threat to human health or the environment and that have new or changing toxicity values or new or changing human health or environmental regulatory standards” (DOD 2019, 15).

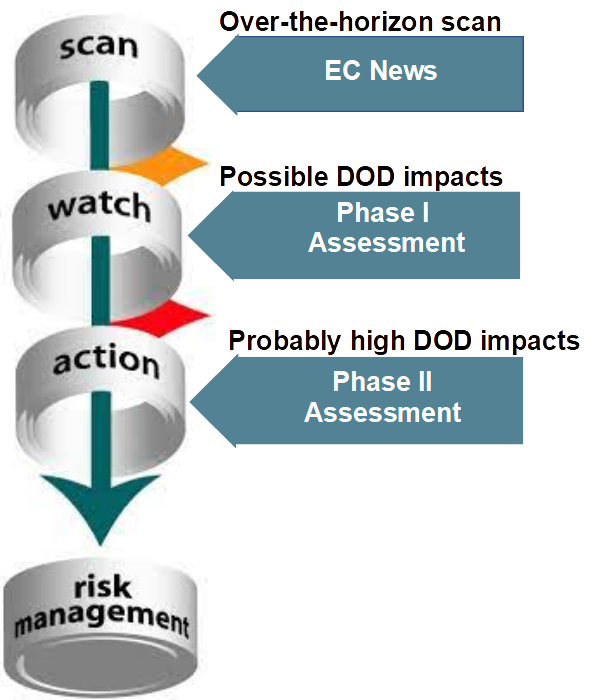

The Chemical and Material Risk Management (CMRM) Program implements a three-step process to identify and mitigate EC risks (Figure 1) (CMRM 2022). The data-driven process leverages current science and subject matter expertise from regulatory agencies, industry, academia, and private organizations. Additionally, DOD is required to integrate Environmental, Safety, and Occupational Health (ESOH) risk management into their overall systems engineering process for all developmental and sustaining engineering activities under DOD Instruction 5000.02 (DOD 2022). Managers must eliminate ESOH hazards where possible and manage ESOH risks where they cannot be eliminated.

Adapted from DoDI 4715.18, 2019

Scan evolving science literature and regulatory actions for chemicals or risk assessment actions that may impact the DOD, human health, or the environment.

Conduct qualitative Phase I assessments to estimate possible impact of screened chemicals to five DOD functional areas: (1) Environment, Safety, and Health; (2) Training and Readiness; (3) Acquisition/ Research, Development, Testing, and Evaluation; (4) Production, Operations, Maintenance, and Disposal of Assets; and (5) Environmental Cleanup. If assessment determines no high risk of impact, chemical is managed on the EC Watch List. If assessment, and subsequent verification, determines high risk of impact, chemical is moved to the EC Action List. The EC Watch and Action Lists are managed through routine monitoring of new and changing toxicity values and/or regulatory standards.

Conduct quantitative Phase II assessments to identify Risk Management Options (RMOs). A Phase II Impact Assessment evaluates likely impacts and costs to the DOD and identifies RMOs, ranging from developing substitute materials to implementing new pollution prevention measures or technologies.

Propose RMOs to DOD’s Emerging Chemicals Governance Council (ECGC) for endorsement. Endorsed RMOs are designated as Risk Management Actions (RMAs). If the ECGC does not endorse an RMO, the CMPM Program will either dismiss the RMO, develop a new RMO, or refine the existing RMO based upon the ECGC recommendations. The CMPM Program monitors the implementation of the RMAs by the appropriate DOD components and periodically reports on the status.

Figure 1. Emerging chemicals “Scan-Watch-Action” process for assessing and managing risks.

Source: Adapted from Cunniff, S. 2009. Identifying Emerging Contaminants. The Military Engineer, January–February 2009. (Cunniff 2009)

4. A New Framework for Identifying and Monitoring CEC

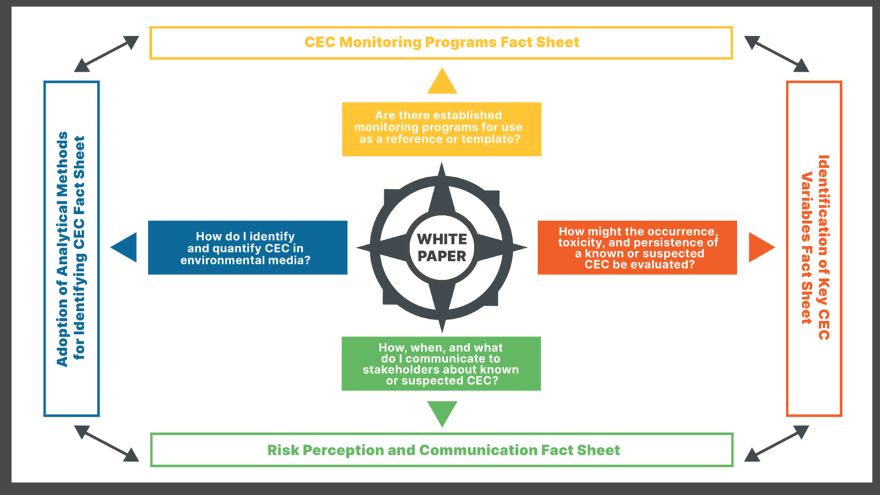

This White Paper summarizes and provides context for the four associated Fact Sheets developed by the ITRC CEC Team to aid state agencies in the development and implementation of a CEC program. The four Fact Sheets were developed from key concepts that the CEC Team identified as vital to the structure of a CEC program. A brief overview of each of the Fact Sheets is provided below and summarized in Figure 2. The Fact Sheets are not intended to be used as a flow chart or linear process. The Fact Sheets provide different information that can be used as part of a CEC program and should be used as needed and not in any particular order.

CEC Monitoring Programs Fact Sheet: This Fact Sheet provides a detailed table of current federal, state, local, and international CEC programs that monitor and/or compile data on CEC. Although most of these current programs are focused on monitoring activities related to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), the information provides a starting point for addressing other CEC. At this time, only a few states have the funding and capacity to establish research programs to evaluate contaminants to determine whether they are CEC. The information in this Fact Sheet can be used as a resource by states that do not currently have the resources or capacity to monitor CEC in the environment. The purpose of the table is to provide information on existing programs in a variety of media that states and other stakeholders can explore and use when formulating their own CEC monitoring programs. States may also consider establishing processes for addressing known CEC such as data sharing across state environmental programs, data mining, expanded monitoring, source identification, and treatment.

Identification of Key CEC Variables Fact Sheet: This Fact Sheet outlines a strategic process for evaluating and prioritizing candidate CEC using the following criteria: occurrence, human health and/or ecological toxicity, and physical-chemical properties. The Fact Sheet provides an initial screening approach to discern whether a CEC is a low, medium, or high priority. A detailed flow chart and supporting tables provide more criteria-related information and data sources. The Identification of Key CEC Variables Fact Sheet also presents a case study outlining the process applied to a hypothetical substance.

Risk Perception and Communication Fact Sheet: This Fact Sheet discusses risk communication for CEC, including the benefits and challenges of communicating risk to internal and external stakeholders. It also provides guidance on appropriate communication and some pitfalls to avoid. A library of risk communication and community engagement materials is included. The Risk Perception and Communication Fact Sheet also presents links to the ITRC CEC Case Study, which provides examples of risk communication strategies and challenges.

Adoption of Analytical Methods for Identifying CEC Fact Sheet: This Fact Sheet summarizes the types of analytical methods that can be used to identify and potentially quantify most CEC, including chemical and chemical classes, biological contaminants, and particulates. The Fact Sheet provides analytical options that can be selected based on how much data, if any, are available for a CEC, including nontargeted and targeted analyses when information on specific chemicals that may be present is not known.

Figure 2. CEC Framework.

Click on an outer rectangle to be moved to that fact sheet.

Source: ITRC CEC Team.

5. Closing

Protecting public health and the environment includes identifying and evaluating CEC present in environmental media even when minimal information is available. By doing so, state agencies can evaluate potential risks posed by CEC, prioritize CEC based on exposure and potential toxicity, and communicate critical information to the public and other stakeholders. Developing such a program not only helps agencies manage risk but also presents an opportunity to address other issues such as those related to environmental justice. In most cases, understanding and managing CEC is a complex process that requires careful planning and consideration of many factors, as indicated above. To support this process, this White Paper and the associated fact sheets provide a framework that state environmental or health agencies can use to develop a CEC program. This framework is intended to be useful whether or not a state has a CEC program. Overall, understanding and monitoring CEC can provide the information necessary to allow states to take corrective and regulatory action and, ultimately, safeguard public health and the environment.

1 The Risk Perception and Communication Fact Sheet provides some guidance on addressing situations with little data and high potential consequences.

References

CDC. 2022. “National Biomonitoring Program | CDC.” June 23, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/index.html.

CMRM. 2022. “Emerging Chemicals Program Basics.” 2022. https://www.denix.osd.mil/cmrmp/ecmr/ecprogrambasics/.

Cunniff, Shannon. 2009. “Identifying Emerging Contaminants.” February 2009. https://www.denix.osd.mil/cmrmp/denix-files/sites/14/2016/05/02_CMRMD_Article_Mil_Engineer.pdf.

DOD. 2019. “DOD Instruction 4715.18: Emerging Chemicals (ECs) of Environmental Concern.” September 4, 2019. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/471518p.pdf.

DOD. 2022. “DoDI Instruction 5000.02, ‘Operation of the Adaptive Acquisition Framework.’” June 8, 2022. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/500002p.pdf.

EGLE. 2019. “Due Care Obligations.” Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy. May 2019. https://www.michigan.gov/-/media/Project/Websites/egle/Documents/Programs/RRD/Due-Care/EGLE-RRD-Due-Care-Guide.pdf?rev=79e593d455c74612a6af450b61777c9b.

Fox, Radhika. 2022. “Memorandum: Implementation of the Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Fund Provisions of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.” March 8, 2022. https://www.acwa-us.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/combined_srf-implementation-memo_final_03.2022.pdf.

MDH. 2022. “Health-Based Guidance Development Process.” October 3, 2022. https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/environment/risk/guidance/devprocess.html.

MPCA. 2023. “Understanding Emerging Contaminants.” Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. 2023. https://www.pca.state.mn.us/air-water-land-climate/understanding-emerging-contaminants.

NSTC, IWG-EC. 2022. “Update to the Plan for Addressing Critical Research Gaps Related to Emerging Contaminants in Drinking Water.” 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/01-2022_CECPlan_Update.pdf.

USEPA, OCSPP. 2014. “TSCA Work Plan Chemicals.” Reports and Assessments. March 14, 2014. https://www.epa.gov/assessing-and-managing-chemicals-under-tsca/tsca-work-plan-chemicals.

USEPA, OCSPP. 2023. “Prioritizing Existing Chemicals for Risk Evaluation.” Overviews and Factsheets. April 25, 2023. https://www.epa.gov/assessing-and-managing-chemicals-under-tsca/prioritizing-existing-chemicals-risk-evaluation.

USEPA, OEJECR. 2020. “The Environmental Justice Government-to-Government Program.” Overviews and Factsheets. April 23, 2020. https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice/environmental-justice-government-government-program.

USEPA, OW. 2014. “Drinking Water Contaminant Candidate List (CCL) and Regulatory Determination.” Collections and Lists. April 3, 2014. https://www.epa.gov/ccl.

USEPA, OW. 2015. “Monitoring Unregulated Contaminants in Drinking Water.” Collections and Lists. August 3, 2015. https://www.epa.gov/dwucmr.